Faced With COVID, a Desperate Man’s Sobriety, Survival Fell to His Mother When Rehab Center Evicted Him

Posted by admin on

By Kathryn Hurd, Ellie Lightfoot and Whitney Bryen, Oklahoma Watch

Lisa Scruggs figures she’s been to every drug house in Oklahoma City. She was used to finding her son in desperate shape. But on a 100-degree July day in 2020, when Josh called from a rehab facility in Lawton telling her he had been kicked out, she knew this rescue mission was different.

Josh McWhorter, 26, had been addicted to heroin for seven years, nearly costing him his freedom and his life. Weeks earlier, Josh had been caught pawning a stolen guitar to fund his addiction. When he appeared in court high on heroin, a judge in Oklahoma City granted him one final chance to get help. In lieu of jail time, he was required to attend 45-days of treatment, which landed him at Roadback, a state-funded substance abuse treatment center.

“He knew he was going to die if he didn’t go to Roadback. He didn’t want to die,” said Robin Bruno, Josh’s public defender.

But just 10 days into his stay, Josh tested positive for COVID-19. Oklahoma was only months into the pandemic. More than 19,000 Oklahomans had been infected and 416 had died from the virus. Josh called his mom in a panic.

“They’re telling me I have to leave the building,” Josh said.

Lisa hopped in her 2012 Honda CX and drove two hours to Lawton, trying to work out a plan in her head. On the phone, Roadback staff told her Josh was now her responsibility. She could return him to Roadback after testing negative for COVID-19. Until then, she had to quarantine him and keep him sober — something she hadn’t been able to do for six years.

“I’m thinking, the state did all this, the court put him here. So there has to be some backup,” Lisa said.

In 2016, Oklahoma voters approved two measures aimed at decreasing the nation’s second highest incarceration rate by shortening sentences for nonviolent, low-level offenders and increasing access to treatment programs that offer an alternative to prison. In Josh’s case, Oklahoma County District Court Judge Lisa Hammond saw an opportunity.

Hammond contacted a local nonprofit and asked them to find a residential treatment facility with room for Josh. Staff at The Education and Employment Ministry (TEEM), an Oklahoma City-based nonprofit that assists with case management, housing, transportation, treatment and jobs, picked Josh up from jail and delivered him to Roadback.

But when Josh contracted COVID-19, neither the court, the nonprofit nor the treatment facility offered to help. Once again, his survival was left up to his mother.

Lisa arrived in Lawton to find Josh crumpled on the curb outside Roadback’s administration building. He had a 102-degree fever and it showed: he was shaking, his pale skin was bright red, burnt from sitting in the July sun. His tan jeans and teal V-neck were drenched in sweat. He had no phone, no wallet. He was laying on the asphalt, resting his head on two black suitcases he brought from jail.

Before Lisa could get out of the car, Josh said, “I did good mom, I didn’t do anything stupid this time.”

She started to hug him, but stopped herself. Was it safe to touch him, or even be close?

Just weeks before, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt had celebrated the reopening of department stores and gyms, unmasked. Thousands of visitors from across the country flocked to Tulsa for Donald Trump’s first campaign rally since the start of the pandemic. Meanwhile, nursing homes and prisons were on lockdown as the virus spread.

The Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services provided COVID-19 guidelines in the form of frequently asked questions on its website to centers like Roadback, which are certified by the department and receive state funding. Centers were expected to remain open and continue serving clients, according to the website.

There was no direction on how often residents like Josh should be tested for COVID-19 or what to do when someone tests positive.

Lisa’s husband is asthmatic and immunocompromised, so she couldn’t bring him home. All of Josh’s friends struggled with addiction, so that wasn’t an option. Her mind was racing.

“I’m just like, where am I supposed to go, what am I supposed to do?”

Lisa had Josh when she was 23 and decided to raise him and his older brother Nathan in Edmond as a single mom. The boys’ father was addicted to methamphetamines and Lisa couldn’t trust him to be around the kids. Lisa and Josh were extremely close. “He told me everything,” she said.

In high school, Josh became a dedicated wrestler, winning regional competitions and medals that once adorned the walls of his childhood bedroom. He was so devoted to learning jujitsu he paid the tuition by cleaning the mats at the dojo.

Lisa Scruggs’ home is filled with photographs and memorabilia of her son Josh McWhorter. A spare bedroom in her home, where McWhorter once overdosed and was found unconscious on the floor, now houses reminders of him like his jujitsu shorts and a glass photo of him and his mom. A China cabinet features a poem he wrote when he was 7, titled “Who am I?” “I am Josh and cool, who dreams good things, who wants to be good.” (Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch)

Josh avoided drugs until he was about 20, when a breakup sent him spiraling. He was in a string of car accidents, having run-ins with the law. What started as smoking marijuana quickly turned into smoking pain pills and injecting heroin.

A few years later, Josh was caught using a stolen credit card and was incarcerated for nearly 11 months. After he was released, Lisa says he began immediately using again.

She barely slept, always on alert, ready to pick Josh up and save him from trouble. She took him on drug runs, waiting in the parking lot afraid it might be the last time she’d see her son alive.

“You get so caught up in the middle of it that you don’t even realize how far you’ve let things go,” Lisa said.

She felt betrayed. Josh used to protect her. “Now he just led me into the pit.”

One day, Lisa bought him a suit to make a point. “I told him that it had to stay at home because I needed it for when I was going to have to bury him.”

On July 2, 2020, a program director at TEEM named Francie Ekwerekwu transported Josh to Roadback from the Oklahoma County jail. Ekwerekwu recalls how during the drive Josh kept repeating “how much he was ready for change and, hopefully, a new life.”

Roadback is one of 28 Oklahoma residential mental health and addiction treatment centers that receive state funding. Those facilities are overseen by the mental health department, which performs on-site reviews every one to three years, depending on the facility’s most recent report. Reviews were paused during the pandemic.

From July 2020, the month Josh entered and was evicted from treatment, through June 2021, state and federal agencies sent $31.4 million in public money to those centers.

During that span, Roadback was eligible to earn up to $560,934.76 in state funds from the department of mental health, according to Roadback’s contract. Funds are calculated based on services provided to clients like Josh. The state agency did not know how much Roadback received during those 12 months.

The Lawton-based center has been operating since 1951. It opened as one of Oklahoma’s first halfway houses and subsequently started a sister program, Helen Holiday, for women. Today it has sober living apartments, and inpatient and outpatient treatment.

The facility draws clients from across the state, many straight from county jails which in the summer of 2020 were hotspots of infection. According to former staff members, basic safety protocols, such as masking and social distancing, were not put into place.

Staff members at the highest risk, resident advisors who were responsible for monitoring and interacting with clients face-to-face, were not provided with sufficient personal protective equipment. Bea Gutzwiller, a former residential aide, said if they wanted protective gear, they had to use their own $8-an-hour wage to buy it.

Josh’s days at Roadback followed a routine, starting around 7 a.m. He attended nearly five hours of group therapy sessions on topics ranging from anger management to coping with anxiety and depression. In the afternoon, Josh attended Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He floated around the common areas the rest of the day, smoking in the backyard or in his room.

Josh noticed the lack of COVID precautions at Roadback immediately. The staff wasn’t wiping down phones between calls or other surfaces. They weren’t wearing masks.

Within his first days, a staff member asked him where the bug spray was. “You can’t ask an addict where the bug spray is,” Josh told his mother on one of his first calls home. “Some of us will drink and smoke that stuff.”

Yet, Lisa said her son remained committed.

“He said, ‘Mom, even though this place is a shithole, I’m going to work for 45 days, so you can have a break from all of my drama. I want you to be able to have life.”

In his week one progress notes, his counselor wrote: “Josh is predetermined to make this program work. He always has a positive attitude. He spreads wisdom and hope to everyone.”

But three days into his stay, Josh started developing a sore throat and fever. It took Roadback six days to take him to the Comanche County Health Department to be tested.

Josh was the second of at least four COVID-19 cases Gutzwieler observed. The quarantine plan Roadback established after Josh’s eviction involved transforming a windowless storage closet where clients would be required to stay for two weeks.

“It was scary,” said Avery Beaty, another former resident advisor. “I do remember at that time somebody had suggested maybe it’d be a good idea to close it down until they got a handle on what was going on. They decided not to do that.”

It was Beaty who learned from the county that Josh was positive. His Roadback superiors told him he needed to discharge Josh. Beaty, a soft-spoken man, remembers getting a “sick feeling” delivering the news.

“It tore me up when I saw him leave because here’s a guy trying to do the right thing and he’s got to leave because he’s sick,” said Beaty, who struggled with his own addiction.

Josh’s records indicate he was “medically” discharged. According to Roadback’s handbook, a discharged client “shall have plans for outpatient treatment, sufficient medication, and a housing referral.”

In Josh’s case, he got none.

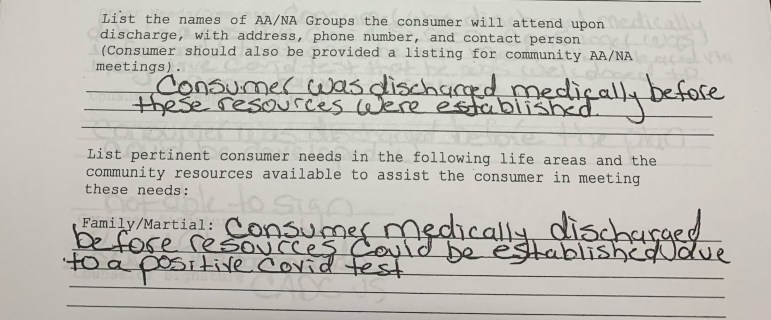

On his discharge paperwork, one section asks for the name, address, phone number and contact person for support groups in Josh’s community. Instead, a handwritten note states “Consumer was discharged before the plan could be developed.”

A similar response was written in a section reserved for community resources to assist with Josh’s needs.

When asked about these procedures, Roadback’s Executive Director Don McGhee said it varies on a “case by case basis.”

Roadback would seek recommendations from outside medical personnel in most instances since it doesn’t have a doctor on site, McGhee said. It’s unclear what access clients get to help from outside medical professionals.

Jeff Dismukes, a spokesman for the state department of mental health, said the agency was unaware of Josh’s eviction from Roadback. The agency is not notified of every discharge from certified facilities, he said.

According to Roadback’s state contract, the department can terminate the agreement if it determines that “the health or safety of the persons served is in imminent jeopardy due to the actions or inactions of Contractor or those under Contractor’s control.”

The department’s governing board renewed Roadback’s certification, and its ability to receive public money, for two more years at a meeting on May 27.

When Lisa picked up Josh, there were still many unknowns about how the virus spread. In the car, she and Josh wore masks, gloves, and wrapped bath towels around their heads. Without any guidance, she decided to bring him to quarantine at the Surestay Inn, which has since been rebranded as the Hemp Hotel with a marijuana leaf on the sign, near the Interstate 235 and I-44 intersection in Oklahoma City. “I didn’t know what else to do,” Lisa said.

When Lisa checked him in, she made sure to leave him with only $7 — enough for a snack from the vending machine, she thought, but not enough to score.

(Left) In November 2017, Josh McWhorter, who struggled with addiction, was sober. (Right) Five months later, McWhorter had started using drugs again. He is pictured at a festival on his mother’s birthday in April 2018. His mom, Lisa Scruggs, said she could always tell when her son was using drugs because he looked malnourished, had open wounds on his face and bags under his eyes. (Photos provided)

The next day was Josh’s 27th birthday. As requested, Lisa brought him a cheese pizza from Domino’s. When she arrived, Josh didn’t come to the hotel door. She called the police, who pounded on the door and called for Josh to answer. He eventually opened the door and said he was drowsy from COVID and hadn’t heard her knocking.

Lisa and the police searched for signs of drug use and found none. The room was organized, toiletries lined up neatly along the bathroom sink. When Lisa left, she remembers Josh standing in the doorway, crossing his arms and blowing her a kiss, like he always did.

After that, Josh stopped answering her text messages. She returned six days later to find his hotel room ransacked with clothes she’d never seen and powdery substances lying around.

Lisa drove frantically around the city looking for her son. That night, she started receiving a string of incoherent messages from Josh. First, sad face emojis, then two hours later, a text saying, “What’s up mom?” But she couldn’t track him down.

A few days later, she received the last text message she’d ever get from Josh: “No matter what happens, I love you, and I’m so grateful for all the things you have done for me and still do.”

The next day, July 20, she got a call from St. Anthony Hospital telling her Josh was in the emergency room. After waiting for hours alone, she could tell by the look on the doctor’s face that Josh was dead.

“I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “ It just feels like somebody ripped your heart out.”

After Josh’s passing, Lisa began a steadfast search for answers. Lisa was convinced that if she could obtain Josh’s records from Roadback, she could show their actions had been illegal, or at least unethical, and cost her son his life.

“Roadback was the place that kicked him out. So that’s the place to start,” she said.

Lisa obtained audio from a hotel worker’s 911 call after finding Josh unresponsive in a bathroom, ambulance records and copies of Josh’s court case. She began piecing together a timeline, from Josh’s first court appearance to his final days. Roadback refused to give her Josh’s file until she underwent a three-month process to obtain a next-of-kin affidavit, which to her, felt excessive. She started calling local attorneys, but the ones she spoke to didn’t seem to think she had a case.

“Nobody wants to stand up for an addict. I think Josh deserves to be stood up for,” she said. “I had to find out what happened and why. The system failed him so many times in the big picture.”

She scheduled a court hearing to be appointed as Josh’s surviving representative in order to get her hands on his documents.

As she awaited her hearing, Lisa kept calling Roadback to inform him of her intentions to secure Josh’s records. On one phone call, the receptionist answered, “Is this about the dead kid again?”

Undeterred, she got the necessary documents and drove to Roadback. This time, she was escorted off the premises and directed to call their attorney, who indicated to Lisa he would cherrypick which records he released to her. She asked him if that was legal, to which he responded, “I think so.”

Judge Hammond said that once Josh was released into TEEM’s custody, he was no longer a ward of the state. Her only option was to put Josh back into the county jail until he recovered, she said, and that did not seem like a good option.

“Would he have survived?” Hammond said. “Who knows with all of the deaths from fentanyl in there, I just don’t know. To me, the better option was to keep TEEM monitoring him and get him help when he was medically cleared.”

According to Jaime Patterson, Director of Diversion Services at TEEM, when Josh was released, the organization wasn’t equipped to monitor him. “No one was prepared for that,” Patterson said.

A spokesman for the mental health department said they were unaware of Josh’s eviction and his death.

No one took responsibility for Josh, except his mother.

“I don’t know if [the records] brought me peace,” Lisa Scruggs said. “It brought some understanding. I guess. And maybe a little bit of peace, but it really just fuels the fire to move forward, to make them be accountable…You just don’t want to see anybody else’s kid go through that.

“Some people need something to make them feel like they’re still fighting for something. Even if it’s not your kids, it’s somebody else’s kid.”

Kathryn Hurd is an investigative reporter and freelance writer based in San Francisco. She currently covers child welfare at UC Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program. Her work has appeared in ProPublica, FRONTLINE, the San Francisco Examiner and KQED. Find more work at www.kathrynhurd.us.

Ellie Lightfoot is a child welfare reporter with the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley’s Grad School of Journalism. They are also a 2022 National Fellow with USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism, and an independent audio and documentary producer, with bylines in ProPublica, FRONTLINE, VICE, and NPR. Find more work at www.ellielightfoot.com.

This article first appeared on Oklahoma Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

—

Oklahoma Watch, at oklahomawatch.org, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that covers public-policy issues facing the state. Republished here with Creative Commons License

—

Photo credit: Whitney Bryen/ Oklahoma Watch

The post Faced With COVID, a Desperate Man’s Sobriety, Survival Fell to His Mother When Rehab Center Evicted Him appeared first on The Good Men Project.